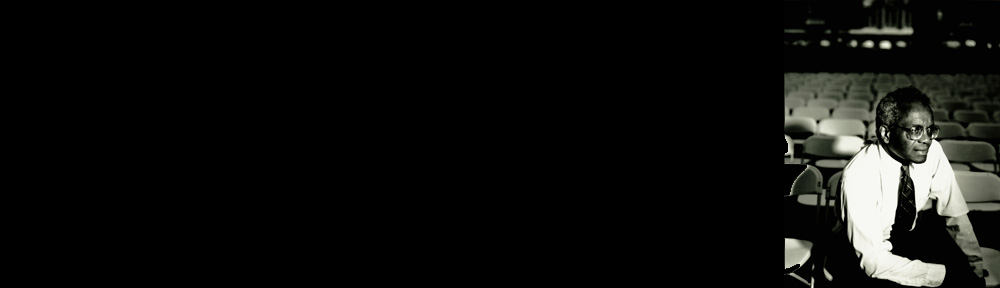

Tributes in Memory of Professor Derrick Bell

Keith Boykin

Writer, CNBC Contributor

October 6, 2011

Shortly after I heard that Steve Jobs and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth had died Wednesday, I learned late last night that my former law professor Derrick Bell had also passed away. All three men touched my life, but none more than Professor Bell.

A few weeks ago, as I have done every September when autumn begins, I remembered a passage from the book of Jeremiah that I first discovered from Derrick Bell: “The harvest is past, the summer is ended, and we are not saved.”

The last few words became the title of Professor Bell’s 1989 classic, And We Are Not Saved: The Elusive Quest For Racial Justice.

Professor Bell was fond of quoting biblical scriptures, Negro spirituals and gospel hymns in his books and in his classroom lectures. When I took his not-for-credit class during his leave of absence protest at Harvard Law School in the 1990-91 school year, it felt as though I was being taught by a preacher as much as an Ivy League professor.

Indeed, Derrick Bell was both. Although he was a man of strong conviction, he was also a gentle soul who spoke softly and kindly and smiled broadly. What drew him to the teachings of Christ, he once wrote, was Jesus’ “courage and vision of radical inclusiveness.” Ironically, those same qualities drew me to Professor Bell, who had the courage to sacrifice his position as a Harvard Law Professor to fight for the radically inclusive idea that the law school faculty should reach out to women of color and other underrepresented groups.

I had the good fortune to be mentored at Harvard by several prominent black professors. Chris Edley, my former colleague from the 1988 Dukakis for President campaign, guided me as I made the transition from politics to law. Charles Ogletree, former Deputy Director of the D.C. Public Defender Service and currently the Jesse Climenko Professor of Law at Harvard, exposed me and other African American students to a series of speakers through a regular program called “Saturday School.” And Randall Kennedy challenged me by raising provocative and controversial ideas for discussion in his classroom.

But it was Derrick Bell who inspired me.

The first black tenured professor at Harvard Law School and the first African American dean at a non-black law school, Bell was legendary on campus. He had worked with Medgar Evers in 1963, worked for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, fathered the formation of Critical Race Theory and literally wrote the book on Race, Racism and American Law. Despite the presence of several black male professors at Harvard, Bell was not satisfied by the inclusion of his own kind and he publicly chastised the institution for failing to hire women of color on the faculty, which ultimately led to his protest and his departure.

Bell taught me the value of “confronting authority,” and it was that inspiration that led me to question the dean of the law school one afternoon as he walked out of a faculty meeting through a group of students who were protesting for diversity.

“Dean Clark, why don’t you come back and talk to us?” I asked. When the dean passed by and refused to engage us, I grabbed my backpack and my sign and began marching toward him. At this point, the dean of the Harvard Law School literally began sprinting across the campus to get away from me and the other students who were following him. A photo of the dean being chased across campus by his students appeared in the Boston Globe the next day. It was my first real experience “confronting authority.”

Later, when I joined a group of 11 students who sued Harvard Law School for discrimination in the selection of its faculty in November 1990, Professor Bell stood beside us at our press conference outside the Middlesex County Courthouse as we announced our lawsuit.

When Professor Bell decided to leave Harvard, a member of our protest movement convinced a young Barack Obama, then the president of the Harvard Law Review, to speak at a rally for Bell. It was the first time I ever saw Obama speak in public, and he praised Professor Bell as “the Rosa Parks of legal education.” Bell, who warned of “the permanence of racism” in his book Faces At The Bottom Of The Well, surely did not imagine that Obama would one day be elected President of the United States. But even after Obama’s historic election, he was wise enough to understand that racism had not disappeared.

In his 2002 book, Ethical Ambition, Professor Bell listed six areas of importance to him about life: passion, courage, faith, relationships, inspirations and humility. From what I could tell, he tried to stay true to all these ideals, but it was his integrity in his relationships that directly affected me.

When I started writing my first book after law school, Professor Bell recommended me to his agent, who helped me to get published. And when I invited him to speak at a rally for black gay men participating in the Million Man March in Washington in 1995, Bell cheerfully agreed.

In many ways, Professor Bell was ahead of his time. He was a heterosexual married black man who publicly supported gay marriage long before any state had allowed it. “That the laws of most countries recognize only unions between a man and a woman is testimony to what a slow and lumbering creature the law can be, and not to any ultimate validity of those laws,” he wrote in 2002, long before Massachusetts or any other state allowed same-sex marriage.

And perhaps it was Bell who predicted, or hoped for, a people’s revolution, like the one that may be forming down on Wall Street. On the day when Republican presidential candidate Herman Cain told America’s unemployed to “blame yourself,” Professor Bell’s message lamenting growing disparities in income and opportunity serves as a rebuke to conservative individualism. “Those disadvantaged by the system who should challenge the status quo are culturally programmed to believe that those who work hard, make it; and for those who don’t make it, well that’s just the breaks,” he wrote.

I believe Professor Bell would welcome the Occupy Wall Street protests taking place across the country. I think he would see it as the long overdue uprising of the masses demanding fairness and justice. “Taking action when you are treated unfairly has risks,” he once warned, “but remaining silent can also be costly.”