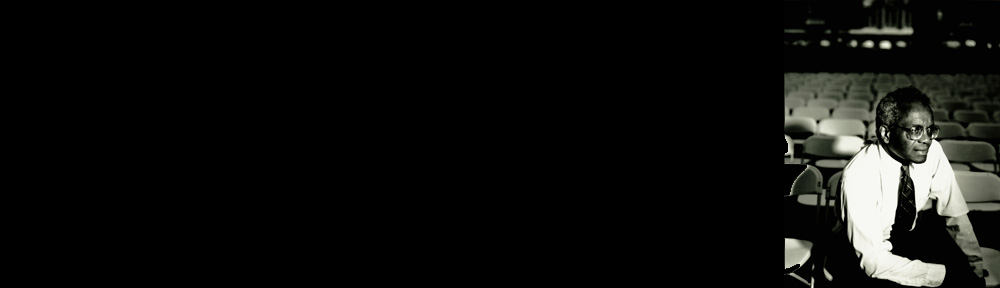

Biography of Professor Derrick Bell

The Early Years: The Making of the Intellectual and Activist

Derrick Albert Bell, Jr. was born on November 6, 1930 in Pittsburgh, the eldest of four children. At an early age, Derrick’s parents, Ada Elizabeth Childress Bell, a homemaker, and Derrick A. Bell, Sr., a millworker and department store porter, instilled in him a serious work ethic and the drive to confront authority.

Derrick was the first person in his family to go to college. He attended Duquesne University, where he earned an undergraduate degree and served in the school ROTC. He then served as a lieutenant in the United States Air Force, where he was stationed in Korea and Louisiana.

After his military service, Derrick entered law school at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, where he was the only black student in his class of 140, and only one of three black students in the school. He spoke up in class, earned good grades and was elected an associate editor-in-chief of the Law Review.

Upon graduation in 1957, Derrick joined the newly formed Department of Justice in the Honor Graduate Recruitment Program and then was transferred to the Civil Rights Division a year later because of his interests in racial issues. His tenure there proved short because his superiors expressed concern over his two dollar membership in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). After Derrick’s refusal to surrender his NAACP membership, senior officials physically moved Derrick’s desk into the Department’s hallway and reduced the docket of cases on which he was assigned. In 1959, after repeated requests that Derrick relinquish his NAACP membership, Derrick instead resigned his position.

Returning to Pittsburgh, Derrick took a job with the local chapter of the NAACP. While there in 1960, Derrick married Jewel Hairston, who was also a civil rights activist and educator. They were married until Jewel’s death in 1990.

Jewel and Derrick had three sons: Derrick III, Douglass Dubois, and Carter Robeson. Douglass was named after Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois and Carter Robeson was named after Derrick’s long-time mentor, Judge Robert L. Carter, and Paul Robeson. Derrick believed deeply in the importance of family and love.

While working in Pittsburgh, Derrick met Thurgood Marshall, who was then the head of the NAACP’s legal arm, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF). Marshall knew of Derrick’s resignation and was impressed by him, so he asked Derrick to join his staff. Derrick accepted on the spot.

From 1960-1966, Derrick worked to dismantle the vestiges of Jim Crow and school segregation in the south alongside Thurgood Marshall, future federal court judges Robert L. Carter and Constance Baker Motley, Lewis Steel, Jack Greenberg and others. Derrick supervised more than 300 school desegregation cases in the South. Upon leaving LDF, he continued his school desegregation work as deputy director of the Office for Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

During this time, Derrick became interested in teaching law, but his initial applications to a few law schools went nowhere. He was then offered a job as the first executive director of the Western Center on Law and Poverty at the University of Southern California Law School where he ran a public interest law center and taught his first classes.

The Protest Years: Harvard and Oregon

In 1969, Derrick joined the faculty of Harvard Law School; in 1971, he became the first black tenured professor on the faculty of the law school. In 1973, Derrick published the casebook that would help define the focus of his scholarship for the next 38 years: Race, Racism and American Law. The publication of Race, Racism and American Law, now in its sixth edition, heralded an emerging era in American legal studies, the academic study of race and the law.

In 1980, Derrick became the Dean of the University of Oregon School of Law, becoming one of the first African Americans to serve as dean. That same year, he published a seminal work Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest Convergence Dilemma, 93 Harv. L. Rev. 518 (1980), in which he argued that white Americans would only support racial and social justice to the extent that it benefits them. His argument that the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown was driven, not by concerns over genuine equality and progress for black Americans, but rather by concerns over the nation’s emerging role as an anti-Communist military superpower, sent tremors through the legal academy.

In 1986, Derrick resigned his position as Dean of Oregon Law in protest of the faculty’s refusal to hire an Asian American female professor. He returned that same year to Harvard.

Soon after Derrick’s return to Harvard Law School, he staged a five-day sit-in in his office to protest the law school’s failure to grant tenure to two female professors of color. With student support, Derrick launched a protest movement at Harvard Law School that received national attention.

Derrick saw the parallels between his work as a civil rights lawyer and a leader for the students’ demand for increased diversity on the law school faculty. In 1990, after years of activism around the hiring and promotion of female professors of color, Derrick took an unpaid leave of absence in protest from Harvard Law School. He would never return. After refusing to end his two-year protest leave, Harvard University dismissed Derrick from his position as Weld Professor of Law.

During this tumultuous time, Derrick met Janet Dewart. As the communications director of the National Urban League, Janet called Derrick for permission to publish one of his fictional stories. This conversation was the spark of a new relationship, and they were married in June 1992.

The NYU Years: A Time of Prolific Writing and Teaching

In 1992, Derrick was invited to join the faculty of New York University School of Law as a visiting professor by John Sexton, his former student at Harvard and then Dean of the law school at NYU.

Derrick loved teaching and was a beloved and popular professor and advisor at NYU Law. He taught his introductory and advanced constitutional law courses in a non-traditional and non-Socratic style, that Derrick called “participatory learning.” This pedagogy builds on the important work of Paulo Freire, and features each student as an active participant in learning. Derrick’s students were empowered, through their participation in a series of mock judicial cases, to teach themselves and one another the law.

In 1995, in honor of Derrick’s 65th birthday, Janet Dewart Bell established the Derrick Bell Lecture on Race in American Society at New York University School of Law. The Bell Lecture has the distinction of being one of the nation’s leading forums on race and the law. The 16th Annual Lecture, scheduled for November 2, 2011, will feature a presentation by Ian F. Haney López, the John H. Boalt Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, where he teaches in the areas of race and constitutional law. Previous speakers include: Charles Ogletree, Charles Lawrence III, Patricia J. Williams, Richard Delgado, Lani Guinier, John O. Calmore, Cheryl I. Harris, Mari Matsuda, Frank Michelman, Anita Allen, Kendall Thomas, Robert A. Williams, Paul Butler, Emma Coleman Jordan, Devon Carbado, and Derrick Bell himself.

During his long academic career, Derrick wrote prolifically, integrating legal scholarship with parables, allegories, and personal reflections that illuminated some of America’s most profound inequalities, particularly around the pervasive racism permeating and characterizing much of American law and society. Derrick is often credited as a founder of Critical Race Theory, a school of thought and scholarship that critically engages questions of race and racism in the law, investigating how even those legal institutions purporting to remedy racism can more profoundly entrench it.

After a valiant battle with cancer, Derrick Bell died on October 5, 2011. In Derrick was an incredibly spiritual man with a deep appreciation for gospel music. As such, it is only fitting that a biblical verse sums up the extraordinary life of Derrick Bell: “Well done, my good and faithful servant.” Matthew 25:23