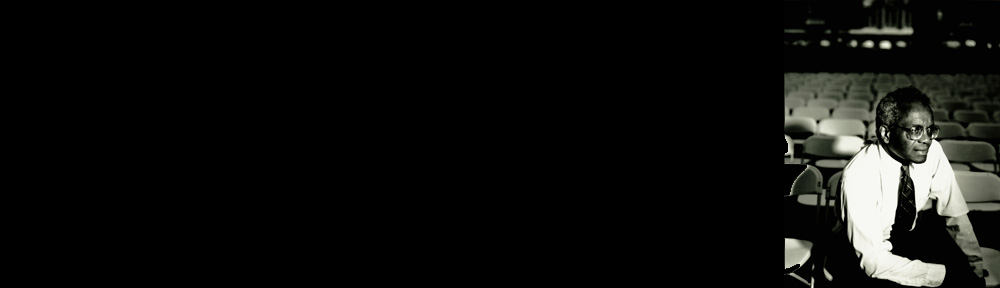

Tributes in Memory of Professor Derrick Bell

Peggy A. Nagae

Former Assistant Dean for Academic Affairs (1982- 1987)

University of Oregon Law School

Founder and President, peggynagae consulting

October 16, 2011

Derrick Bell will be remembered for his scholarship, activism, humanity, and dignity. In the years we worked together at the University of Oregon and the decades of our friendship, I remember “Derrick-isms” that have touched my heart, raised my blood pressure and made me (and continue to make me) be a better person. He was the best boss I had ever had, but even more than that he was the change I wanted to be in the world.

Among many of his lessons, Derrick taught me, “In the end we will not be judged by the results we attain, but by the quality of the struggle we maintain,” words he spoke in a time when we did not reach our goal. His words have stayed with me, especially during times when it seemed fruitless to point out the “obvious” to those for whom it was obviously not obvious. Why bother? At an ABA Minority Lawyers Conference, I was listening to a panel, on which a ULCA law professor, Richard Sanders, argued that black law students accepted at first tier schools under affirmative action should decline and attend second-tier schools. I was floored and ready to get up and stomp out, but as I sat there fuming I heard Derrick’s soft but insistent voice in my thoughts, “Miss, you must speak out.”

I sat on my hands and muttered four letter words to my friend, but stayed for the Q & A, then got up and stood in line to respond. I thought Sanders’ reasoning obviously flawed but realized that the younger attorneys of color in front of me, who no doubt felt the same, were too polite to say so and perhaps too young to remember what it had been like to fight our way through school. In true Derrick Bell style, but with much less grace, I told Professor Sanders that if the audience were from my baby boomer generation we would have been booed him and his patently racist premise off the stage. I accused him of taking no responsibility as a professor because he refused to call law schools to task for not teaching students—all students— not simply to pass a bar exam but to excel as lawyers. As I spoke I felt as though I was “channeling” Derrick, albeit with much less finesse. It was through his example that I have gained the courage to speak up and to fight the fight.

In our talks about law school as a place for transformation, civil rights and righting wrongs, we talked about responsibility. Early on in my years working for him, Derrick said, “Asians are too quiet. I hired you as my assistant dean to be a role model and to speak out.” I agreed with him: we had been taught that the nail that sticks up is the first to get hammered. My voice—already too strong for some Asian Americans—became stronger. I spoke out more and said what was on my mind, in my role of assistant dean for academic affairs when law students came to me on a variety of issues, as the chair of the dean’s representative advisory group when campus-wide issues arose, and in speeches and presentations I gave in the re-opening of one of the World War II Japanese American internment cases.

I grew up on a farm in Oregon where we lived in poverty largely because my parents had been incarcerated during World War II. Consequently, they did not teach me to speak out, but rather to get my education and do twice as good as white students so I could escape the farm and earn my way in a much better environment. Derrick had faced his share of adversity, and at every turn, he had not hesitated to speak out.

Derrick’s challenge spurred me on and gave me much-missing support for honing my louder and more vocal message about justice and equity. Derrick demanded more than simply speaking out. “You have to do what is right regardless of the personal cost,” he constantly instructed. And so, again his words called me to action.

This time I was with more than 60 other academic leaders at the Harvard Institute for Educational Management. We were listening to a tenured professor from the Harvard Business School when he used the term “Jap.” At first, I sat in stunned disbelief. Then, in a nano-second I realized that, yes, I had heard him correctly. I also realized that I was the only Asian American in the group and that it was unlikely anyone else would speak out.

Without further thought, and again in true Derrick Bell form, I raised my voice and stopped the class. “Don’t use that word; it is derogatory, offensive and insulting.” The Harvard professor, whose name I have forgotten, stopped talking, peered up to see where that voice came from and then said, “Some of my clients are Toshiba, Sony and Panasonic.”

Not only did that professor never apologize, neither did the director of the program, another Harvard professor, who was in the audience and heard the exchange. In fact, when I told the director that I did come to teach Harvard professors what terms were offensive, he called me arrogant and walked away.

I telephoned Derrick, described the situation and without missing a beat, he responded: “You did the absolutely right thing and do not ever expect a job offer from Harvard!”

Having Derrick a telephone call away meant we could debrief situations, and he could give me instant advice, support, and wisdom, much like he did for many, many others. While no longer a physical phone call away, his voice is now within me and will remain there.

When Derrick and I worked side-by-side at Oregon, there were big episodes like the time Derrick resigned as the dean! But there were also so many smaller moments—the day-today acts of courage—which I continue to cherish.

I remember, for example, watching Derrick wash the plastic cups after a reception because we had so little money and I stood there wondering how many other law deans would do that. I remember our daily jogs in the early morning hours with his and Jewel’s two dogs, when we talked about our families or he gave me the latest details of his Geneva Crenshaw creation. Or, when I would get his latest article with a handwritten note: “If I can do this, you can, too.”

Bold and gentle; strident and compassionate; race-conscious and all- inclusive, Derrick lived in the paradoxes, never forgetting the lessons from his past. He never forgot that it had been student protests that “encouraged” Harvard to hire him, their first African American tenured professor. He never forgot his upbringing: his father working as a garbage collector and his siblings’ struggles. He reached the top of the academy, but regardless of fame and fortune, being at the pinnacle of success meant reaching back and bringing people along, be they students who would become law school deans or those who cleaned law school classrooms. I love you, Derrick.